The "new Piafs"...

When Édith Piaf died in 1963, aged only 47, she left a huge hole at the heart of the French music industry. The previous three years had seen the chanson gradually eclipsed by the oncoming horde of yé-yé singers, at least as far as the media were concerned, although there would always be room on the airwaves and in the country's leading music halls and theatres for the stars of a more traditional form of French popular music. Piaf had been in ill health for several years but her sudden passing was still a shock that left the country reeling. Forty thousand people turned up to attend her burial in Père Lachaise; many thousands more flocked to the shops to pick up one of her many classic recordings. Piaf may, to paraphrase her most famous song, have had nothing to regret, but her fellow citizens very much regretted that she was no longer alongside them.

Perhaps inevitably, Piaf's departure from the stage engendered any amount of debate as to who might possibly replace her. Within the chanson world from whence she sprang, there were two possible contenders, although both had their own unique styles and an appeal that was markedly different from la môme Piaf.

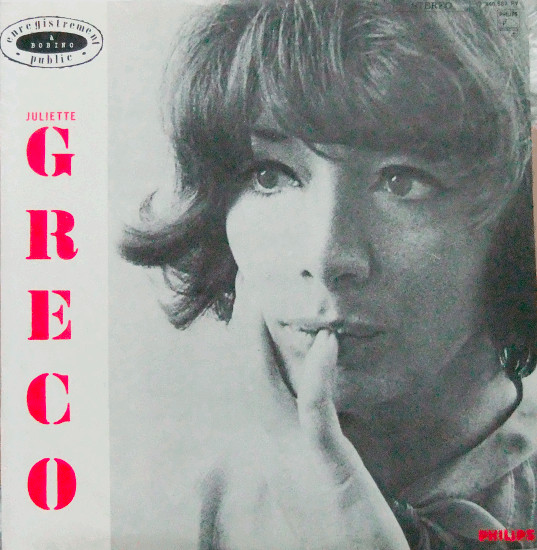

Juliette Gréco had long time been Piaf's rival, sharing her international appeal and even, in her early days, some of the same repertoire (Piaf had turned down Charles Aznavour's "Je hais les dimanches" but was furious when the young Gréco turned it into hit, recording it herself "to teach that girl how to sing it!", as she screamed at Aznavour). However, Gréco's appeal was always more cerebral, more focused on the primacy of the text and while she certainly inhabited her material, her performances lacked the intense emotion that permeated every note of a Piaf recital. Having spent the past half-decade sidetracked in a film career, Gréco's popularity in France was at this point on a downward curve, and although she would make a commercial recovery later in ther decade, she never attained the level of mass popularity that Piaf had enjoyed.

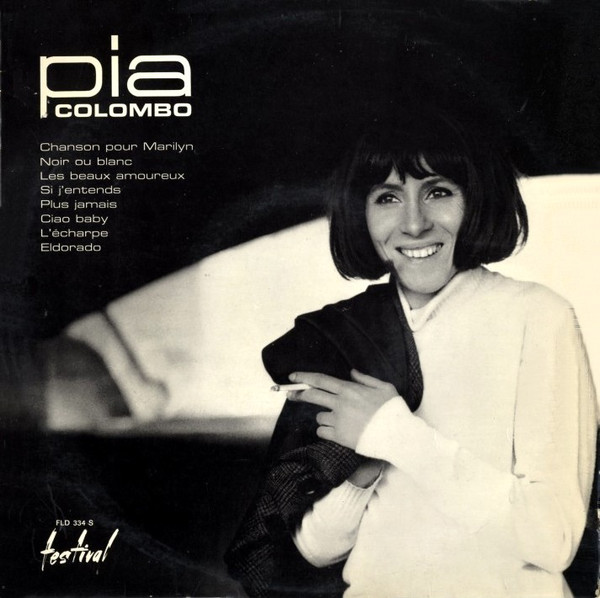

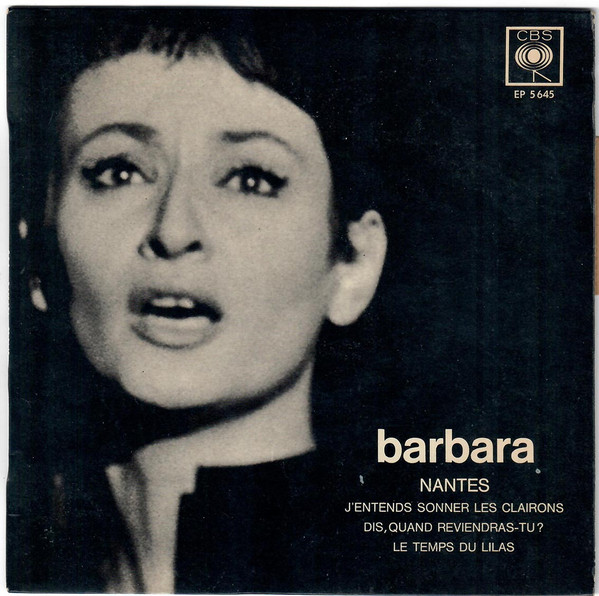

Pia Colombo had been one of the few singers who had dared to take on Piaf on her own territory, taking her own version of the classic "Milord" to market alongside Piaf's timeless recording. Piaf inevitably won the battle for sales, but Colombo was unbowed, carving out her own niche in the world of la chanson with a string of impressive releases through the sixties, most notably "L'écharpe", written by her former husband, Maurice Fanon (who also recorded it himself). Lacking the driving ambition that set Gréco (and Piaf) apart, Colombo never made much impact beyond the borders of France, although her recordings seldom dipped in quality. Somehow though, she was never quite taken to heart of the public in the way that Piaf had been.In the year following Piaf's exit, a fresh contender broke through after a very long apprenticeship in Brusels and Paris. Barbara had spent many long years performing in tiny cabarets to minuscule audiences, first singing the works of Jacques Brel, Georges Brassens and others but gradually finding her own style as a songwriter with an intimacy and a depth of emotion that was all her own. After a couple of critical favourites that had nevertheless failed to sell - most notably "Dis, quand reviendras-tu?" - she exploded to prominence in 1964 when she performed the newly-written "Nantes" on television, prompting a rush of buyers looking for a record she had not yet even recorded. Her first self-penned album, Barbara chante Barbara was a remarkable piece of work that spoke from her heart directly to the hearts of her listeners, establishing an unbreakable bond between singer and audience that is practically unmatched anywhere else in the music industry. But Barbara was not a new Piaf - she was the first Barbara: a pianist who sang, clad in black, with a repertoire and a style that was uniquely hers.

Barbara's rise to the top flew in the face of the prevailing musical trends of the year. The British Invasion had begun, led by The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, both of whom visited France in 1964, throwing out a robust challenged to the dominant yé-yé stars, although the yé-yé storm continued unabated. Cute, pretty, young girl singers were now ruling the roost and aging chansonnières were yesterday's news - not that anyone told Barbara... But who among the yé-yé girls could plausibly be held up as a nouvelle Piaf?

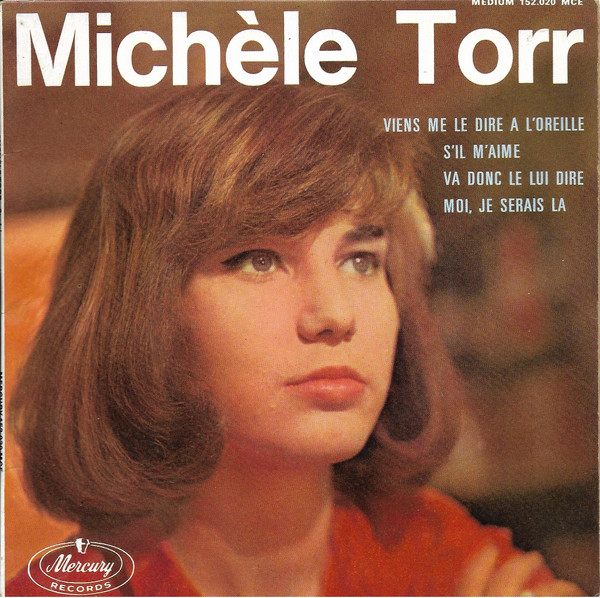

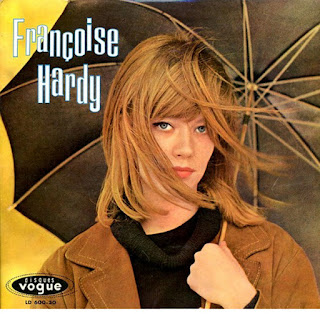

Certainly not Sylvie Vartan or Sheila, the two leading lights of the year. Both had their charms, for sure, and a style of their own, but neither could really be accused of injecting their life and soul into their recordings. The same could be said for the newly-emerged France Gall, whose vocal abilities were limited, although she certainly knew how to make her limitations work in her favour. Françoise Hardy was a better candidate - she had the international appeal, at least - but her wallflower laments were in a whole different class from Piaf's cries from the heart. Among the lesser lights, there was Michèle Torr, the yé-yé girl who could really sing but while she would, in the decades to come, establish herself with the adult audience, at the time she was competing fiercely in the yé-yé marketplace. The yé-yé girls made joyous music, no doubt about it, but only one of them had the bottle to take on something out of Piaf's repertoire, the pint-sized French answer to Brenda Lee. Although Jocelyne's usual repertoire was drawn directly from American girl group sources, on her first (and as it turned out, only) LP she turned out a surprising - and surprisingly good - rendition of Piaf's French version of the theme tune from the film Exodus, although she never followed it up.

Piaf of course had attracted an older audience than the teenagers flocking to the yé-yé standard, so perhaps it was not surprising that there would be no new Piaf emerging from their ranks. Instead, the best contenders all emerged with a slightly more sophisticated repertoire aimed squarely at an older audience. Sylvia Clément had been recording for a couple of years before Piaf's death and her 1964 release "Mon Dieu, écoute-moi" was a reasonable enough effort but it didn't sell and her career never really caught fire. Sabrina put a belting cover of Piaf's "Hymne à l'amour" onto a 1974 EP but the arrangement owed more to Jackie Trent's UK rendition ("If You Love Me") than to the diminutive titan of French chanson and the record promptly died the proverbial death.

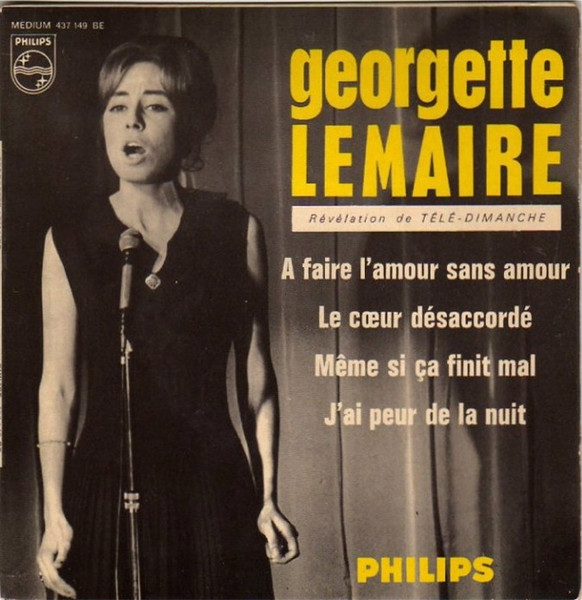

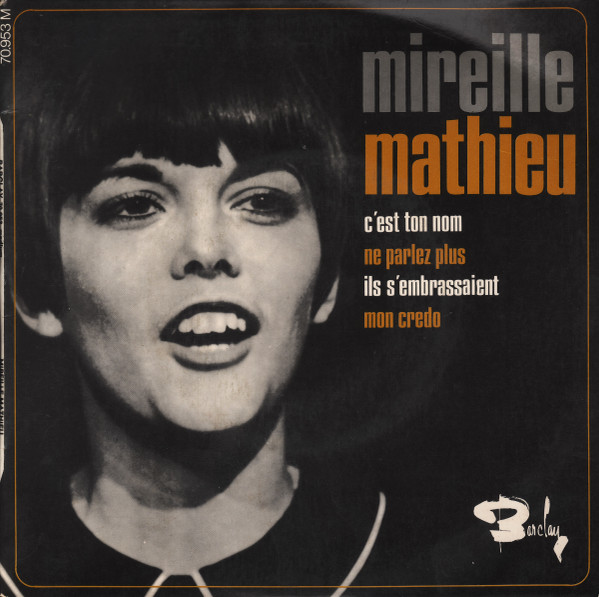

In commercial terms, Lemaire would be completely eclipsed by another singer who emerged - incredibly - from the very same talent contest. Mireille Mathieu could turn on Piaf's trademark warble in her sleep, and her voice had a range and a power that few could rival, although it has to be said that her approach - or that of the producers and managers who directed her career - was the polar opposite of Piaf's soul-baring style. Mathieu's repertoire was pure pop, plain and simple, and she never made any claims to offer anything else. Her debut EP sold hundreds of thousands of copies thanks to the strident charms of "Mon crédo", the first of dozens of hits she would enjoy before finally running out of steam in the late eighties. While many of her hits came via original material, she was not above reaching out to international sources, enjoying a cross-Channel smash with a French-language cover of Engelbert Humperdinck's "The Last Waltz" ("La dernière valse") in 1967.

The bottom line, of course, was that Piaf was irreplaceable. While subsequent years would produce many remarkable talents, some of whom - such as gospel-soul-pop singer Nicoletta - had both the vocal firepower and the soulful passion, but the fact was, Piaf was a one-off, a unique combination of talents that nobody could hope to replicate. There will never be another like her. Nearly sixty years on from her drug and alcohol hastened demise, she remains a touchstone for French chanson, an icon known and admired around the world. Her entire catalogue remains in print today, with new anthologies appearing as regularly as the seasons. Why? Just take a listen...

You can read more about Piaf, and many of the other singers mentioned here - and much more besides - in my newly-released book. Feel free to grab a copy here: BOOK

Comments

Post a Comment