Contact: Françoise Hardy

In 1962, the Vogue label held a series of auditions for new singers, with the lucky ones being launched to market via a series of EP releases in the "Contact" series. The generic title was one that the company used for several years for the debut releases by new singers - among other performers to make their debut in this way were girl group Les Gam's (1962) and singers Alain Dumas (1963) and Pascal Danel (1964). Some of them enjoyed moderately long careers (although not necessarily with Vogue) while others were typical "here today, gone tomorrow" ephemeral pop singers. In the summer of 1962 though, Vogue definitely hit the jackpot.

Françoise Hardy had previously auditioned for the Pathé company, who at the time were making good money off the back of the country's second-biggest rock 'n' roll outfit, Les Chats Sauvages. Despite her obvious talent, Pathé rejected her, thinking she was another, probably inferior singer in the vein of Marie-Josée Neuville, the one time "collégienne de la chanson" who had enjoyed a short run of hits for the label during the mid-to-late fifties (the fact that Neuville's hits had since dried up probably helped frame the label's thinking). Like Neuville, Hardy wrote her own songs, but at a time when most French teenage singers were getting hits by covering American tunes, this was not necessarily seen as a strength.

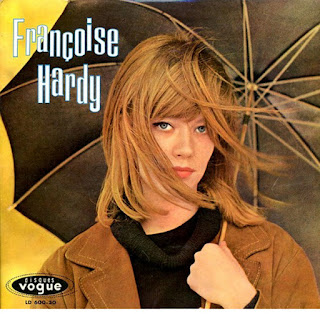

Pathé's loss was Vogue's gain. Signed during that 1962 talent drive, to a label that had recently lost Johnny Hallyday to Philips and was keen to make good its loss as quickly as possible, Hardy was rushed into the studio to cut four songs for her debut EP release. The label was determined to launch her with a hit, and to that end commissioned an adaptation of a 1958 US song as the lead track. Bobby Lee Trammell's "Uh Oh" was not a well-known tune (even in the States, it had been sent to market as a B-side; it had been reissued in Canada in 1961, which may be how it came to Vogue's attention) but it had a certain commercial... something. With French lyrics penned by professional songwriters Jil et Jan (also responsible for several of Hallyday's early releases), "Oh oh chéri" seemed a good prospect in a marketplace that was not yet labelled "yé-yé". Hardy was no doubt somewhat frustrated at having the song foisted on her, but she did get to include three of her own songs (on which she shared credit with producer-arranger Roger Samyn) on the rest of the EP, which duly appeared on Vogue as EPL 7967 in July of 1962.

Despite a decent advertising campagin in the newly-launched Salut les copains magazine and a smattering of radio play, initial sales were slow and the record resolutely failed to catch fire. The song was certainly catchy, and Hardy's winsome vocal gave it a winning appeal but even so, the record ate dust behind the latest releases from Johnny Hallyday, Richard Anthony and Sylvie Vartan.

And that might very easily have been that, had radio programmers and listeners not turned their attention instead to the self-penned material that comprised the remainder of the release. "Il est parti un jour" was nothing to write home about, but "Je suis d'accord" was certainly a catchy enough effort to make it worth giving a bit of a push. The record was duly repromoted with a different sleeve promoting the newly favoured tune, although the catalogue number remained unchanged.

The new marketing ploy was at least partly successful. Airplay was better this time around, but teenagers queuing up to buy the record were still notable by their absence. A buzz was however beginning to build around the final song on the record, a plaintive wallflower ballad titled "Tous les garçons et les filles". It was nothing like the proto-yé-yé records that were taking Sylvie Vartan to the top, nor was it anything like the rock 'n' roll sounds made by Vartan's new boyfriend, Johnny Hallyday, although ironically enough, it did have a touch of Marie-Josée Neuville about it. More to the point though, it tapped a similar feel to Richard Anthony's massive-selling "J'entends siffler le train" ("500 Miles") and it carried a lyric of loverlorn loneliness that spoke to the heart of teenage girls all over the country.

Vogue's promotion team duly got to work for a third time, printing up sheet music, getting the song into the reportoire of as many bandleaders as possible and commissioning a special "Scopitone" clip for the video jukeboxes that were found across the country.

The massive promotional drive did the trick and by October, the song was on the airwaves and in the charts, rising steadily through the winter to top the charts in Billboard and on Radio Luxembourg, although oddly it never rose above #5 on the teenage favourite Salut les copains hit parade (partly because the chart was still varying its format at the time - it would not settle down until early 1963). Two further EPs and an album were rushed out in its wake, with all three selling strongly for several months. With interest spreading across the country's borders, Hardy recorded her smash in German ("Peter und Lou") and in Italian ("Quelli della mia età") and enjoyed big hits across both the Rhine and the Alps, with combined sales topping the million mark. Hardy also recorded an English version ("Find Me A Boy") which somehow flopped completely, although a belated issue of the original French version did make the UK (and the Brazilian) charts early in 1964, having already done so during 1963 in Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Israel, The Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland.

Hardy would never again record anything that sold quite as well as her breakthrough hit, although she would enjoy a long - very long - string of hits across the globe. Fêted by Mick Jagger, courted by Bob Dylan and eventually married to Jacques Dutronc, her fashion sense and chic style kept her in the public eye for most of the sixties, with her ever-inventive singles, EPs and albums withstanding comparison with anything from the giants of the era. During 1963, she would rank among the top ten best selling artists in the world, and while she could not and did not maintain that level for long, she remains one of the few artists from the yé-yé years whose new album releases continue to chart and to make ripples around the world. Thank heaven that the Vogue promotions team back in 1962 were so persistent...

You can read more about Françoise Hardy's recordings - and much more besides - when my book is released tomorrow. Feel free to grab a copy here: BOOK

Great article, tgank you. Would you say the Scopitone helped with the breakthrough?

ReplyDeleteit certainly helped. I suspect the breakthrough was radio play on "Salut les copains" but once the record started to move, the Scopitone would have done the rest.

ReplyDelete