Who says girls can't sing rock 'n' roll?

The French music industry of the fifties - as elsewhere - was as full of chanteuses as it was chanteurs. True - most (but not all) of the musicians, songwriters and producers were men, as they were in thne rest of the world, but French music halls and cabarets had always been as open to the female voice as they had to male performers. Indeed, it was not uncommon for male singer-songwriters to make their initial breakthroughs thanks to the women who chose to sing their wares. This tradition went way back - think of the partnership between Rip and Jeanne Aubert in the twenties - and even recently emerged stars like Léo Ferré, Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel owed their start to the support of Catherine Sauvage, Patachou and Juliete Gréco respectively. Rock 'n' roll though, was something else.

When the new wave of teenage music first hit France, it was seen as just a fad and ripe for covering by music hall and cabaret performers, men and women alike. The results were, well, just what one might expect, although probably no worse than some of the whitebread efforts churned out by established stars in the US (Georgia Gibbs? Teresa Brewer?), although generally the men came off better than the women. However, as these bandwagon-jumping efforts were swept away and replaced by the real thing, the women got pushed to one side. Virtually all the front line rockers pouring out of America were young, testosterone-fuelled men and rock 'n' roll was seen pretty much everywhere as a boy's game (the pioneering works of Ruth Brown and LaVern Baker notwithstanding). So it would be in France, where all of the early running was made by young men, from the wild and uninhibited Johnny Hallyday to the smooth and polished Richard Anthony. What place in this new world for the girls?

Aside from the likes of Dalida and Petula Clark, both of whom were fairly comfortable with rhythmic music, few of the established stars could cut the mustard. There were however a few chanteuses from the jazzy side of the tracks who proved able and willing enough to make the effort. Foremost among them was Nicole Croisille, who slipped a cover of Ray Charles' "Hallelujah I Love Her So" ("Dieu merci, il m'aime aussi") onto her debut EP in 1961. The rest of her repertoire was pretty much jazz, although she returned to Brother Ray for her third release, which featured a cover of his "This Little Girl Of Mine" ("Tout ça dépend du gars!") alongside a nice version of Teddy Randazzo's "Let The Sunshine In" ("Laisse entrer le ciel"). She had the vocal chops but none of this was really rock 'n' roll.1960 and the early months of 1961 had seen a number of rock 'n' roll-styled records released in France by female singers but none of them came anywhere near the noise being whipped up by, say, Johnny Hallyday or the newly-emerged group, Les Chaussettes Noires. That changed in April 1961 with the debut release of the Hungarian-born Hédika.

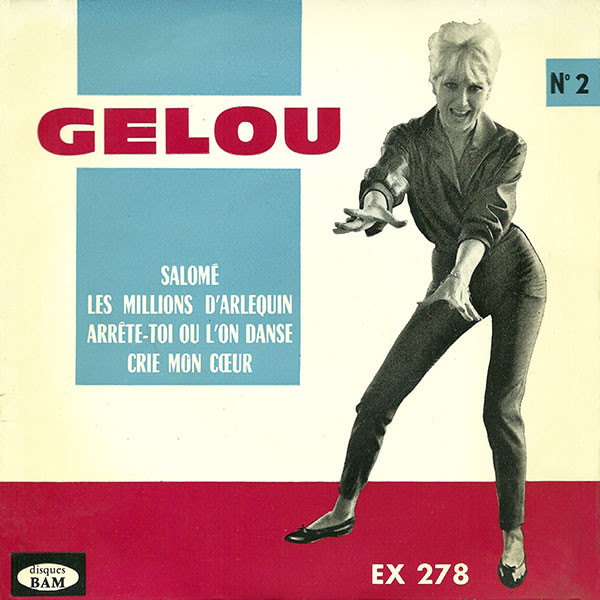

Gélou continued recording through 1962, landing a minor hit with a cover of Ray Charles' "Unchain My Heart" ("Délivre-moi") that lost out on the sales to a rival cover by Richard Anthony before her career ground to a halt. As with Hédika, her style was too upfront, too, well, masculine to survive in the French marketplace of the early sixties. She would return to action under her real name in 1965 with a trio of self-penned EPs, her hair now at a length unlikely to spook the marketplace, but nobody was really interested. Ahead of her time, Gélou slipped quietly into the history books as the sixties drew to a close.

Once again though, the record was little more than a cult hit, with Paquin's performances failing to hit home with an audience only just getting used to Elvis. She tried again with a second EP that rang the bell with the excellent "Mon mari c'est Frankenstein" (adapted from an obscure early Phil Spector production, "You Can Get Him - Frankenstein" by The Castle Kings). Once again, the Scopitone allowed her to show what she had to offer - twisting away to a rocking beat while clad once again in trousers. Quite what the country's moral guardians made of her is unsure, although as she had earlier (before her first record) shocked television viewers by appearing nude (from behind) for a total of fifteen seconds in the telefim L'exécution, perhaps they were prepared for anything.

Paquin certainly had the chops, but despite the quality of her records, the breaks never came. She walked away from the music industry in 1962 to become a journalist, although she returned for one final, unremarkable EP in the mid-sixties. Like Gélou and Hédika, she was more than capable but she was in the wrong place and at the wrong time. So too was perhaps the best of the early rockeuses - Belgian singer and guitarist Jackie Seven.

With this out of her system, Seven followed through with a second cracking EP release, this time with cover art that lived up to her public image. The standouts this time were covers of Little Tony's Italian hit "Pericolo blu" ("Non, ce n'est pas dangereux") and Fats Domino's "Shu Rah" ("Ça va"), both tasty rockers with punchy saxophone and electric guitar slicing through the air as Seven gave her all at the microphone. Out in front of an audience, the singer pulled out the stops and she was no less full-on in the studio, but clearly, despite some reasonable sales, the music industry had no idea what to do with her. Given a chance to strut her stuff on television, she was left without her guitar to front the stage like a (sort-of) conventional chanteuse, although she still managed to turn on the appeal for a raucous version of her twist hit.

Like the others, Seven was too raucous for public consumption and after just two releases, she hung up her guns. Like Paqun, she would make a low-key return in the mid-sixties for an EP that was widely ignored and that, to all intents and purposes, was that. Apart from Brenda Lee, there were few singers anywhere in the world operating successfully in this territory (Janis Martin, anyone?). Lulu was still three years away and in school; across the Atlantic, Lee's biggest (and more popular) rival was Connie Francis, and there was little of the raucous about her. In any case, the wheel was about to turn, as the twist ushered in a lighter-hearted, less frantic form of rock 'n' roll and Gillain Hills ushered in the rise of the yé-yé girls. What was needed was someone who could bridge the gap between rock 'n' roll and the new yé-yé wave. By the end of 1961, that singer had emerged in the shape of the young Sylvie Vartan.

Having established herself with a style mid-way between rock 'n' roll and more conventional pop, Vartan pushed the boat out a little on her next few releases. Her second EP mixed rocking covers of Ray Charles' "What'd I Say" ("Est-ce que tu les sais?"), Bobby Lewis' "One Track Mind" ("Un p'tit je ne sais quoi") and Elvis Presley's "Don't Be Cruel" ("Sois pas cruel") with the teen fluff of Hayley Mills' "Let's Get Together" ("Nous deux ça colle") and her fourth cut loose on The Ikettes' "I'm Blue" ("Gong gong") and Roy Orbison's "Dream Baby (How Long Must I Dream)" ("Cri de ma vie") while smoothing things out with a pair of covers from The Shirelles, one of the American girl groups whose style would be such a huge influence on the yé-yé girls who would follow.

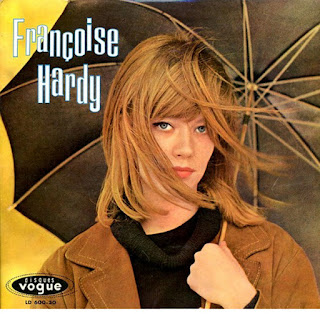

It was the latter which would eventually win out and by the time that Vartan went to town on Little Eva's "Loco-Motion" ("Le locomotion"), the yé-yé revolution would be complete, with Vartan established as the queen of the yé-yé girls forever more. But she - and the many other firls who rose to prominence in the sixties, would owe much to the pioneering work of the rockeuses who preceded them. Hédika, Gélou, Nicole Paquin and Jackie Seven would never become the household names that Vartan, Sheila and Françpise Hardy would be, but they fully deserved their places in the history books for their sterling work in laying the foundations for everything that would follow.

Comments

Post a Comment