The first yé-yé girl?

"

American singer April March once famously claimed that yé-yé was the best music that there is, which might be overstating it although there is no denying the music's considerable appeal. For all that though, there is considerable debate about what yé-yé actually is - a problem compounded by the fact that the term has become decidedly elastic over time. There are plenty of things that yé-yé is not - a mix of French chanson with rock 'n' roll, for example. Strictly speaking, yé-yé is not even uniquely French - there were yé-yé singers in other French speaking countries such as Belgium, Switzerland and - to a lesser extent - Canada, and a healthy yé-yé scene developed in Spain as well. Nor is yé-yé an exclusively, or even mainly, female phenomenon; there were plenty of male yé-yé singers too, from Richard Anthony and even Johnny Hallyday on through Frank Alamo and Hervé Vilard to lesser-known but still worthy names such as Jamy Olivier or Michel Paje. Still, to the wider world of record collectors, it is the yé-yé girls of the sixties - Sylvie Vartan, France Gall, Sheila etc - who stand out as the most enduring representatives of the yé-yé era. But who was the first yé-yé girl?

Female singers had been dabbling with rock 'n' roll style material in France since the mid-fifties when Line Renaud covered LaVern Baker's "Tweedlee Dee" (1955) and actress Magali Noël recordeed Boris Vian's deathless "Fais-moi mal, Johnny" (1956). However, the first chanteuse to properly get to grips with the material was probably the Egyptian-born star Dalida, whose Italianesque accent and love of exotic material had made her the biggest star in the French firmament in 1957. Having shot to the top of the back of a string of hits of Italian origin, at the end of 1958 she switched tack and had a go at The Shepherd Sisters' "Alone", rendering it in French as "Je pars" and landing a monster hit over the winter. While Dalida would never hitch her fortunes exclusively to one style, she dabbled in further rock 'n' roll-styled covers over the next few years, including Paul Anka's "You Are My Destiny" ("Tu m'étais destiné"), The Teddy Bears' "Oh Why" ("Mon amour oublié"), Floyd Robinson's "Makin' Love" ("T'aimer follement"), Brian Hyland's "Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka-Dot Bikini" ("Itsi bitsi, petit bikini"), The Drifters' "Save The Last Dance For Me" ("Garde-moi la dernière danse") and, best of all, Bobby Darin's "Dream Lover" ("J'ai rêvé").Dalida was a hugely charismatic singer and a major teen idol in the immediate pre-rock 'n' roll era, but although she retained a large and loyal following across the following three decades (and beyond!), her exotic image and essentially adult approach mean that she does not quite fit the mold when looking for the origins of the yé-yé evolution. A better suggestion might be English singer Petula Clark, whose own version of "Alone" had been blown out of French waters by Dalida's cover (as had her version of Jodie Sands' "With All My Heart", which Dalida recorded as "Gondolier"). In an effort to stop Dalida from stealing more of her hits, Clark's record company suggested she begin recording in French, arranging a trip to Paris where Clark fell in love with her local publicist, prompting her to abandon her London home and set up a new career as a singer in France.

Hills' first two records for 1961 continued this uneasy blend of old and new, mixing tunes penned by the likes of Charles Aznavour (who would be responsible for penning any number of yé-yé hits during the early sixties) with covers of material ranging from Sophia Loren's "Zoo Be Zoo Be Zoo" ("Zou bisou bisou") to Bobby Rydell's "Good Time Baby" ("Allons dans les bois"), the latter of which absolutely set the template of the music we now know as yé-yé, although Hills was beaten to the punch by a rival (and slightly earlier) version by Richard Anthony. By the end of the year, she had her style down pat, dropping the last trappings of exotica and emerging from the chrysalis as a fully-formed yé-yé butterfly with superb covers of Helen Shapiro's "Walking Back To Happiness" ("Je reviens vers le bonheur") and The Shirelles' "Mama Said" ("En dansant le twist").

Hills's rise had not come without its mis-steps. Earlier in 1961, she had been booked to provide the female vocal reponse to Frankie Jordan on a cover of Floyd Robinson's "Out Of Gas" ("Panne d'essence"). Hills pulled out at the last minute, so the gig went instead to producer and arranger Eddie Vartan's sister, with the resultant smash hit vaulting the newly-emerged Sylvie Vartan to stardom. Still, things worked both ways. When actress Dany Saval was unable to team up with the country's leading (and best) rock 'n' roll outfit Les Chaussettes Noires for the soundtrack of the film Les Parisiennes, Hills stepped up to the plate to duet with the band's frontman, Eddy Mitchell on the exuberant "C'est bien mieux comme ça" (another Aznavour co-write), which went on to become the biggest hit of her career.

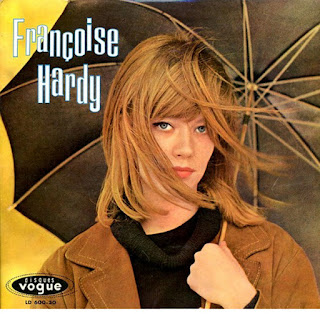

Issued in the sumnmer of 1963, the record sold comfortably if unspectacularly, with Hills' lengthy absence from the airwaves having left her far behind the triumphant Sylvie Vartan, Sheila and Françoise Hardy, all of whom owed a little something to Hills' pioneering efforts. Later in the year, she recorded "Une petite tasse d'anxiété", a duet with Serge Gainsbourg - his first yé-yé composition - that has frustratingly never been released commercially on record or CD, although the pair did film a video for televison use...

It could have been the start of a near perfect relationship but instead, Gainsbourg went off to write hits for France Gall, to win Eurovision, write the score for the teleflm Anna and then craft a series of pop smashes for Brigitte Bardot, for Jane Birkin and for himself. Hills meanwhile cut a final EP for Barclay, with the results surfacing in January 1964. Again, all four tracks were self-penned but sales were disappointing. A switch to the Disc AZ label in 1965 saw her covering The Zombies' "Leave Me Be" ("Rentre sans moi") and The Lollipops' "Busy Signal" ("Tut tut tut tut") but Hills was by now tired of playing the pop star. She returned to the UK, when she cut a final record (1966's "Tomorrow Is Another Day") before returning to acting with a role alongside David Hemmings and Jane Birkin in Michelangelo Antonioni's Swinging London classic Blow-Up. Further film roles followed, including one in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange before she walked away from the industry and relocated to the US to work as a book and magazine illustrator.

All in all, it had been quite an interesting career. While film buffs still look fondly on her work in Beat Girl and Blow-Up, it is probably her recordings that attract the greatest interest today. "Zou bisou bisou" was used on the soundtrack to the hit TV series Mad Men, while "Tut tut tut tut" found its way into the Netflix series The Queen's Gambit. In 2018 she was tempted out of retirement to make some new recordings, culminating in the 2021 album LiLi. Her classic French recordings continue to be reissued, and as international interest in the yé-yé era continues to grow, Hills' pioneering work as the very first yé-yé girl of all continues to find a new audience.

All in all, it had been quite an interesting career. While film buffs still look fondly on her work in Beat Girl and Blow-Up, it is probably her recordings that attract the greatest interest today. "Zou bisou bisou" was used on the soundtrack to the hit TV series Mad Men, while "Tut tut tut tut" found its way into the Netflix series The Queen's Gambit. In 2018 she was tempted out of retirement to make some new recordings, culminating in the 2021 album LiLi. Her classic French recordings continue to be reissued, and as international interest in the yé-yé era continues to grow, Hills' pioneering work as the very first yé-yé girl of all continues to find a new audience.

Comments

Post a Comment