A song for Easter....

Back to business after a two week break for the Easter holidays, which got me thinking about the fact that while Christmas songs a two a centime, songs about Easter are few and far between. Outside of gospel and religious music, anyway... This is certainly true in British and American pop music, but it seems to be true in French pop music too. Although there is this one...

The early seventies were the protest years in France, as the hope engendered by les évenements of May 1968 gave way to the frustrations of the Pompidou presidency. While student protests began to fade in the US after the shootings at Kent State University, in France barely a week went by without striking workers, marching students and sometimes violent clashes with the forces of law and order. Hardly a likely environment in which to find the country's primary religious icon, and yet...

In 1970, Philippe Labro was a novelist and journalist with a long career in television and a recent feature film, Tout peut arriver to his credit. Labro was fascinated by the atmosphere of the times and in particular by the hippy movement that he had observed at close quarters in California. The long-haired peace and love generation seemed to Labro to be closer in spirit than most of contemporary society to the ethos of the message preached by Jesus Christ and his disciples in the New Testament. The idea of the Christian icon as a hippy proved irresistible to Labro's pen and in a short space of time he had written the lyrics for a song. But who would he get to sing it?

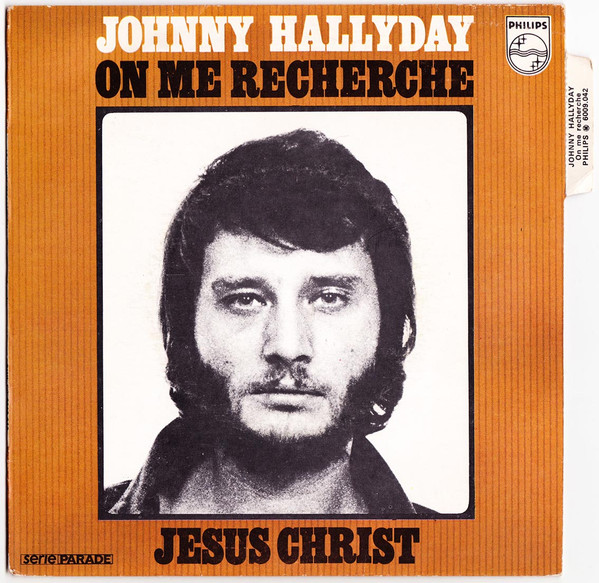

Johnny Hallyday was nobody's idea of a revolutionary hero. Caught on the wrong side of the barricades in 1966 during his semi-manufactured spat with long-haired beatnik singer Antoine (the latter had castigated Hallyday as a sellout in his smash hit "Les éluubrations d'Antoine"; Hallyday had responded in kind with the reactionary "Cheveux longs et idées courtes"), l'idole des jeunes had however been at least briefly attracted to the hippie movement, covering Scott McKenzie's "San Francisco" and contributing his own flower power anthems "Fleurs d'amour et d'amitié" and "Je suis l'amour". He was also still, a decade on from his debut, the biggest pop star in the country. As far as Labro was concerned, only Hallyday had the stature to take on the song. He contacted Hallyday's brother-in-law, bandleader and arranger Eddie Vartan, who took away the lyric and sold the idea to the singer. Hallyday duly composed a suitable melody, Vartan handled the arrangement and in no time, "Jésus-Christ" was in the can. Labro also knocked off a lyric for the country-rock flipside, "On me recherche" and the single (Philips 6009042) was ready to go.

Labro has subsequently claimed in interview that it was not his intention to cause a scandal, but one wonders quite what he expected would happen with a song whose hookline proudly proclaimed "Jésus-Christ est un hippie". Imagining a modern-day Christ (just as the creators of Godspell would do), Labro's lyric described him as having been born in where else? - San Francisco, playing the guitar, smoking marijuana, sleeping rough in train stations, hanging out with bare-breasted women, fighting the police in Chicago, healing the sick at Woodstock and being on the run from FBI officers determined to catch and crucify him. Hardly the stuff that hit records were made of, then or now, and it was unlikely that French radio would go anywhere near it. Independent station RTL (broadcasting from Luxembourg) likewise gave it short shrift (station boss Jean Farrant denounced it as being both sacrilegious and and in bad taste), but over at rival station Europe No. 1 (broadcasting, via a complicated subterfuge, from Germany), Lucien Morisse was more than happy to play a song that his rival would not touch. Within hours, the song was on the air, being spun six times a day for maximum impact before the country's censors intervened and the song was banned from the airwaves on 29 April.

A ban on airplay rarely did a record any harm, especially if the song had already been repeatedly broadcast before the ban came into force. By the time the censor's axe fell, the song was already on the lips of listeners across the country and well on its way into the charts, where it rose rapidly to become one of the biggest sellers of the year. It was helped along its way by the highly commercial bad man ballad on the flipside, which scooped the airplay that its running mate was denied, making for a genuine double-sided hit.

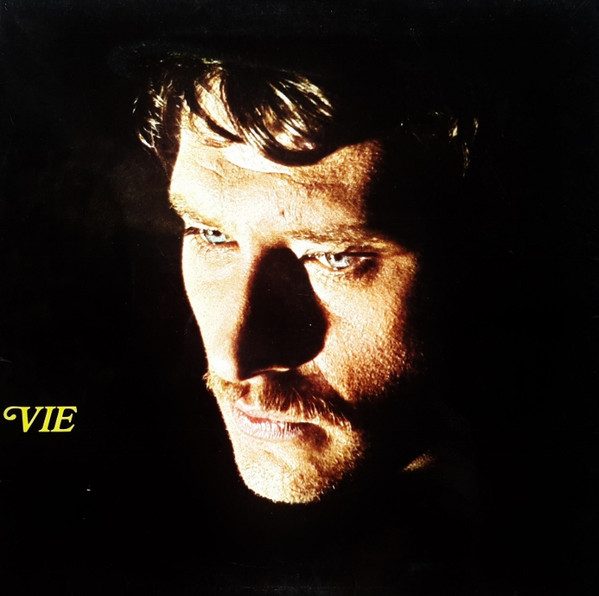

In one stroke, Labro had repositioned Hallyday on the right side of the barricades, and the pair went on to create a whole album of topical songs, issued in December as Vie (Philips 6397018). With his former tormentor Antoine by now peddling mainstream Europop ditties like "Ra-ta-ta", Hallyday had convincingly turned the tables and metamorphosed into a long-haired protest singer for the age, as heard on such efforts as "C'est écrit sur les murs", "La pollution", "Rendez-moi le soliel" and, best of all, the uplifting "Essayez", another smash hit single early in 1971. However, not everyone was convinced... and rightly so, as Hallyday's later political pronouncements in favour of Nicolas Sarkozy would make clear. Still, it worked for a while, even if Jacques Dutronc, never one to take anything seriously, couldn't help but send up Hallyday's efforts on his late 1970 single "L'ane et au four et le boeuf est cuit" (Vogue 45 1778).

Hallyday and Labro would collaborate again on the 1971 album Flagrant délit and would sporadically work together over the subsequent decades. Labro would also work wirh Serge Gainsbourg for Jane Birkin's 1975 album Lolita Go Home but songwriting would only ever be a minor aspect of his lengthy media career. Hallyday of course went on, and on, and on, the once and future king of French pop whose career was only finally ended when he succumbed to lung cancer in 2017.

You can read about Johnny Hallyday's early years - and much more besides - in my newly-released book. Feel free to grab a copy here: BOOK

Comments

Post a Comment